No. 107

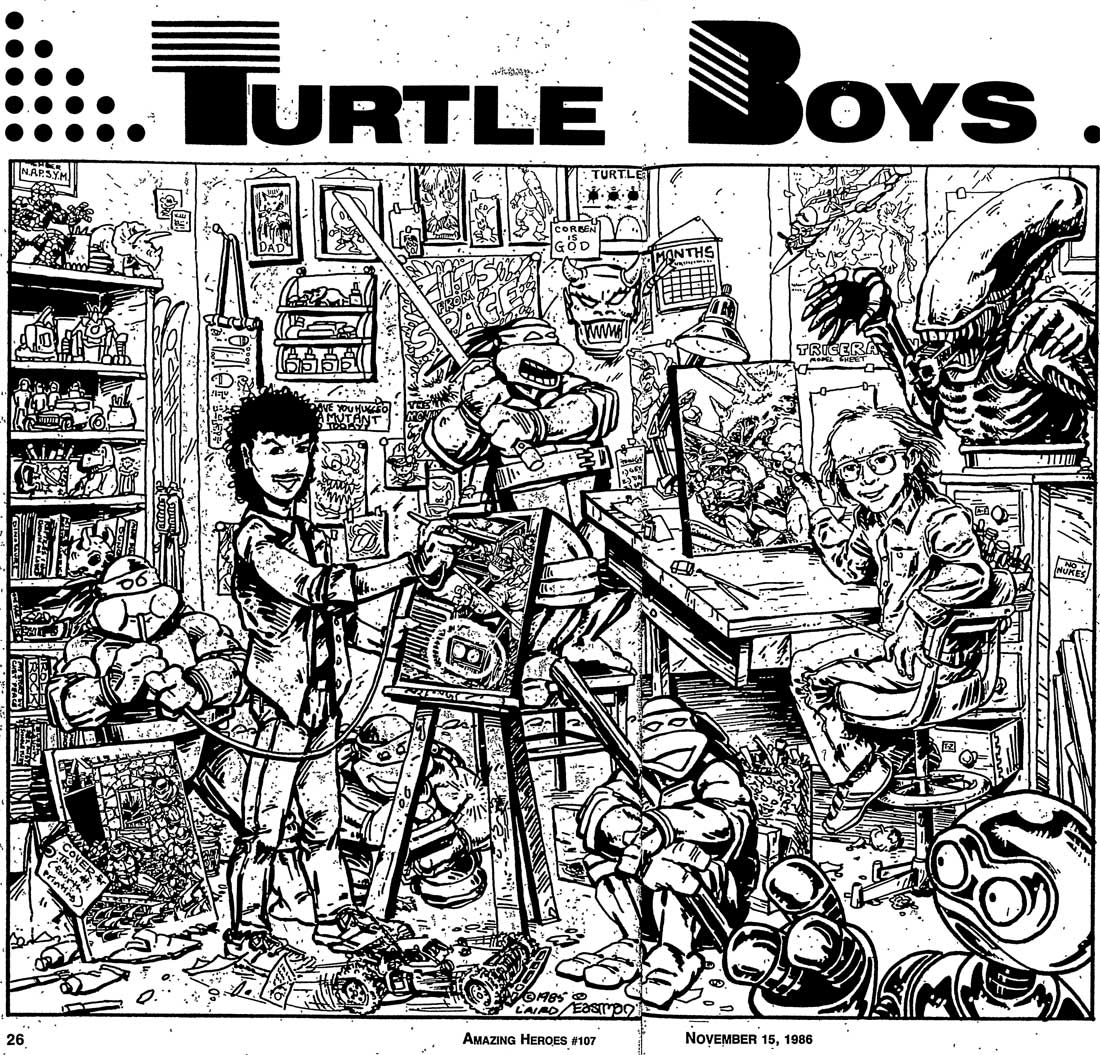

November 15, 1986 The Turtle Boys

An in-depth conversation with the creators of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

by THOM POWERSNot only are these boys hot, they’re getting hotter all the time. They’re Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird, and they are the men behind Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Originally no more than a parody of Frank Miller’s Ronin, Turtles has achieved an unprecedented level of success in the direct market in a remarkably short time. Not only is the book the best-selling “independent” comic – no other non-Marvel/DC title is even in the same ballpark – but the Turtles have branched out into role-playing games, three-dimensional miniatures, and How to Draw the Turtles publications. Hell, they’ve even made the Kestugo ads seen in comics of the ’70s obsolete now that the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles training Manual is a regular series.

“We need to talk to these guys,” we said, and dispatched Thom Powers to speak with Eastman and Laird about their past, their present projects, and their plans for the future. This interview was conducted in mid-October and transcribed by Powers. – MW

AH:Could you fill me in on your academic background, what you were doing before the Turtles, and how you know each other?

PETER LAIRD: I went to the University of Massachusetts from 1972 to 1976. After that, I was a freelance illustrator and did editorial illustrations. I met Kevin in 1972 * as a result of him running across a magazine with some of my work in it.

(*clearly a typo but I am presenting these interviews as they were printed – KE , October 2018)

AH: Were you working in comics at this time?

LAIRD: No, I was a great comics fan. I hadn’t broken in at all, though. I had done a few self-publishing things like mini-comics and actually went down to Marvel’s offices once – and was shown the door, basically. Comics were always something I wanted to do; I just hadn’t found the right combination of circumstances yet.

KEVIN EASTMAN: I went to a couple of different schools for about a year. On my own, I couldn’t afford to do much more than that, trying to keep up with the rent and so on. But I started writing and drawing my own stories and selling some to Clay Geerdes’s Comix Wave and Brad Foster’s Goodies. After that, I ran into Peter and we started working on projects together. First Fugitoid and then the Turtles.

AH:Can you talk about the evolution of the Turtles?

EASTMAN: Your turn, Pete? We take turns telling this story.

LAIRD: Well, we were living in Dover, New Hampshire, sharing a house. One night we were sitting around with the tube on, just doodling away, and Kevin came up with this sketch of a turtle standing upright with a mask and a Nunchaku strapped to his forearm. It was really goofy, so I had to do one of my own. Then Kevin said if we can have one, then why not four, so we did a drawing of four with different weapons. I inked that, and Kevin called them Ninja Turtles. Then I said, “If ‘Ninja Turtles’, why not ‘Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’?”

AH: Were you fed up with the whole teenage mutant trend at the time? Was this a result of reading 16 comics that were all the same?

EASTMAN: I’d agree with that. We always read comics and, at that time, there were quite a few teenage superheroes. It seemed all the superheroes were teens.

AH: If you were both really poor at this time, how did you come to produce this comic?

LAIRD: Well, we scraped up some money. Kevin had some income tax money, about $500, and his uncle was generous enough to lend us another $700 or so. *

(*not entirely accurate, lol, but I am presenting these interviews as they were printed – KE , October 2018)

EASTMAN: My uncle was really into it. We presented it to him like a business, showed him a mock-up cover, advertisements, stuff like that. My uncle used to sell art supplies, and he’s always been fairly interested in what I was doing. He was great about it.

AH: This was the first idea you felt strongly enough about to self-publish?

LAIRD: Well, we came up with Fugitoid first, but while we tried selling that to other companies, we always thought of doing Turtles ourselves.

AH: Did you think it would just be a one-shot?

LAIRD: We were open to do more, but it was really a one-shot to begin with.

EASTMAN: It was a one-shot because we weren’t sure if we could sell the first one.

AH: What were your first circulation figures?

LAIRD: Three thousand. That’s how many we could afford to print, using every bit of money that we had at the moment.

AH:Was that just a case of picking up the phone and finding the first printer that you could?

LAIRD: Basically. A lot of people ask us why we did the oversized version first. That happened because of a mistake. We went to the printer in New Hampshire and we brought this book of free TV facts. I don’t know if they have them in your area. They’re printed on newsprint and bound by staples or glue. So we took this to the printer and said, “Can you do this? We want a glossy cover and newsprint inside.” Bu we didn’t tell him the size, and he just assumed that we wanted it like the TV facts book.

EASTMAN: It just goes to show how naive we were about the whole business. We didn’t contact any distributors or anything. We didn’t know how the business ran. So we took out an ad in The Comics Buyer’s Guide and planned to sell the books one at a time through the mail.

LAIRD: We finally realized that it wasn’t going to work that way. It took too long and we couldn’t afford full page ads in the CBG.

EASTMAN: Actually, it was from the full-page ad that distributors called us.

LAIRD: I think Longhorn of some Texas distributor called first.

AH:Didn’t Longhorn go out of business?

LAIRD: Yeah. [Laughter] We found that they were interested, but that they didn’t want to pay what we wanted. We were asking 90 cents a book, and they wanted to pay 60 cents – a 60 percent discount, which is pretty standard. Eventually, what we did is sell 90% of that print run at that discount. They sold a lot faster than we thought; we expected to be sitting on them for a long time.

EASTMAN: We broke just about even on the price, too. I don’t think we made any money at all, maybe just a couple hundred dollars.

LAIRD: We almost immediately went back to press with a second print run of 6000 using the money that had come back from the first printing. There was quite a demand for [the book]. If we had been able to solicit for it, we probably could have been able to sell a lot more. Like Kevin said, we were pretty naive, just stumbling around trying to figure out what to do.

AH:When did you really know that this was a success?

LAIRD: I think it was around #2. That was around December, 1984. We finished #2 and sent it off to the printers and our orders were 15,000.

EASTMAN: Peter and I were still working our regular jobs even after the first book came out.

AH:Were you doing other artwork or manual labor?

EASTMAN: Basically manual labor, the old standard, regular paycheck, 40 hours a week. It let us pay the rent and still do drawing.

LAIRD: As it happened though, Kevin had moved back to Maine and I’d moved to Connecticut with my wife, so all the artwork for #2 was done through the mail. That’s why it took us so long to get it out.

AH: How exactly do you two collaborate?

LAIRD: We come up with the story together, then Kevin starts working out the panel forms real rough and making script notes while I write the full script. Then the thumbnails are enlarged and reproduced as rough pencils on the finished size paper.

EASTMAN: We both ink, a little here, a little there, so that we try to get half of each of us on every page. Our styles are similar, with slight differences, and I think that they accent each other.

AH:I was told that you use a special kind of paper that gives your work its dark look.

LAIRD: Yes, the brand name is Craft-Tint. It’s the same stuff that Roy Crane used for Buzz Sawyer, the newspaper strip.

EASTMAN: In black-and-white books you have your black line and white background. We wanted to do something with gray tones, something different from the normal black-and-white books. Cutting zipatone was out of the question. You buy it in sheets with different patterns and then you keep adding different sheets to different characters. Our process is really easy and it really gave us a different look. It also stems from the Frank Miller parody. Inker Klaus Janson every once in a while would do a shade and I could never figure out how he’d do it. Again, another sign of how naive we were.

I can remember when we talked with distributors about doing a second book. They said, “You know, your book’s fine, it’s really picked up in sales, but the only way it will sell really well is if you go to color.” That’s something that we couldn’t even think of – we were having enough trouble scraping up the money to put out the title in black-and-white. Se we said we’d take our chances. Now it’s gotten to the point where we could go to color if we wanted to – we have with the graphic novel – but people really like it the way it is. A couple of years ago, [readers] said they would read anything but black and white.

AH: You did a color Turtles story with Richard Corben in issue #7. How did that come about?

EASTMAN: That was the first color Turtles story [and was] a personal fantasy for me. I was always a Corben fan. It was received well, but people still like the black-and-white.

AH:Besides Corben, who are some of your other influences?

EASTMAN: Well, Corben’s the strongest. Kirby, I always read Kirby. Vaughn Bode is another one. Currently, Frank Miller, for some of his layout and panel design.

LAIRD: I share with Kevin an influence from Kirby. He’s the main man as far as comics are concerned. I encountered Barry Smith’s Conan during my formative years. Russ Manning, another inspiration.

AH:From what I understand, you were both mainly artists. How did your writing develop?

EASTMAN: Even now, I have trouble considering myself as a writer. Maybe I’m a real ambitious amateur. I always wrote. I used to read a lot of undergrounds. It seemed like most of these people just wrote whatever came into their heads, which inspired me to write short stories. Today we do really lengthy Turtles stories, which is fun, but I still love the short story, something totally removed and different. I just go nuts and see what happens.

LAIRD: Like Kevin, I’ve never really thought of myself as a writer, but I’ve liked to tell stories since even before the Turtles. Turtles was the first real intense storytelling experience that either of us had. It’s been a real learning experience keeping characters straight and coming up with stories on a regular basis.

EASTMAN: I get a real charge out of doing the initial panel break-downs. We’ll jam out a one page summary first, then do the planning, choreograph fight scenes. Going back to Corben and the real cinematic way he looks at things, his presentation is a real influence. Writing a story is like making a movie and choosing shots.

AH:Are you influenced by film?

EASTMAN: Oh, very much. One of the benefits of cartooning is we can doodle while we watch TV. Now VCRs and video shops are so popular, I rarely go to the theater anymore. I can watch zillions of movies at home while I ink or make notes or doodle on my lap board. Peter watches at least as many films as I do, and it’s a big influence on our work.

LAIRD: It’s well known that there are a lot of similarities between film and comics.

EASTMAN: Comics is really a simplified director’s chair.

AH:Getting away from Turtles for a moment, what does the future hold for some of your other books?

LAIRD: Fugitoid may have a future, we may do a second issue.

EASTMAN: He’s kind of in limbo right now. The Turtles take 110% of our time. We’d love to do something with [Fugitoid], but at this point we’d have to find an artist that could handle it.

AH:How do you coordinate handling both the business end and the artistic end of Mirage?

EASTMAN: The business is real interesting. We’re learning on both ends, helping each other along the way. We’ve learned how to deal with distributors, do shows, and organize things, along with how to do the books more easily and which systems work better. Right now, we’re probably as efficient as we’ve been. We’ve just hired a business coordinator, a young woman named Diane Berube. She’s organized us, helped keep us on track.

AH:Does the business ever interfere with your art?

LAIRD: Ooooooh.

EASTMAN: Oh, yeah, there’s a lot of stuff to keep track of.

AH:Do you regret that? Would you rather be working for another company?

EASTMAN: No.

LAIRD: No. The benefits are far greater.

EASTMAN: Far Greater.

LAIRD: The freedom to make your own decisions without an editor hanging over our head.

EASTMAN: Pete will call me up and say, “We gotta go down to the office today to do ten different things. At those times, I just want to stay at home because I’ll be in the middle of a story or something. But I wouldn’t have it any other way.

AH:What about this First Comics project?

LAIRD: They’re reprinting our first three issues in color.

EASTMAN: We did the colors and there’s twelve new story pages.

AH:How did this arrangement come about?

EASTMAN: Well, we were doing a show in New York City and [First Comics’ Publisher] Rick Obadiah was there. We had just done a Munden’s Bar story for Grimjack, and we went to lunch with Rick, who was talking about expanding the graphic novel line. They’d just put out the Elrick graphic novel and Chaykin’s American Flag! [The project] seems like it’s moved fast, because the graphic novel itself will be out on the stands in November.

AH:Will that open any new markets for you?

LAIRD: First is getting into Waldenbooks and B. Dalton and other bookstores.

EASTMAN: We’re hoping that, if this goes over well, we’ll go right into the next series.

AH: How did your gaming book come about?

LAIRD: We were approached to do that. Kevin Siembieda of Palladium Books had known about the Turtles and said that he’d be interested in developing a game and leasing the license. We liked his approach, so we went with it. He had someone write the game and we did the illustrations and an eight-page story.

EASTMAN: That first one is a real hot seller. It turned out to be one of the most successful licensing ventures. The second would be the Dark Horse miniatures of the Turtles. It was neat to see three-dimensional figures of what we created on paper.

AH:What about this martial arts book?

LAIRD: We gave Solson the right to produce those. The only connection we have is the characters.

AH:Are the drawings yours?

LAIRD: No.

EASTMAN: We didn’t do anything but the cover. Actually, for the How To Draw the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles book, which was the first one, we did rough sketches, panel layouts, breakdowns, plus the black-and-white work for the cover. Other than that, we’re pretty removed from the stuff.

AH: Any regrets about licensing and people messing with your characters?

EASTMAN: Not really. There have been a few instances when it’s been disappointing, but nothing major. Only disappointing in that we made a bad business move.

LAIRD: Whenever we license anything we keep a final say in our contract.

AH:So what’s the future for Mirage and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles?

LAIRD: Well, it’s looking pretty bright. Kevin will agree that we shouldn’t be too verbose about this, but you’ll be seeing Turtles in areas other than comics a lot more. As for the Turtles comics themselves, there will be six books next year – four regular issues and two micro-series – and another graphic novel from First if the first one sells well.

EASTMAN: We’d like to keep expanding, doing outside things. Like Michael Dooney’s Gizmo, which was really selling well for us. Mike’s really turning out a quality comic. Another artist that’s working for us is a gentleman by the name of Ryan Brown. Brian is going to be producing a book called Rockola. He was doing a Bloom County-type strip in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. He had a lot of success with that. This will basically be the first rock-and-roll oriented comic book, so we’re pretty anxious to see how it’s received.

AH: Do you receive a lot of submissions?

EASTMAN: Well, recently. Tell him why, Pete.

LAIRD: We’re doing a book called Turtle Soup next year which will be composed of Turtle stories written and drawn by other people.

EASTMAN: Giving them a free hand to do what they want with the Turtles. To drop some names, Steve Bissette, Stan Sakai, Joshua Quagmire.

AH: You’re working with Quagmire?

LAIRD: Well he’s thinking about it. He’s definitely doing something for Grunt.

EASTMAN: We’re doing another book kind of like Turtle Soup called Grunt. There’s still no release date for it yet. It’s going to be all anthropomorphics, dealing with them as foot soldiers in different time periods. Pieces of history, from the Civil War to cavemen to outer space. We want to capture the theme of the foot soldier, the grunt, using animals.

AH:Are either of you martial artists?

LAIRD: Well, we’re both black belts in karate.

EASTMAN: He’s full of shit. [Laughter]

LAIRD: We’ve both had an interest in martial arts. We’ve taken classes in karate and judo.

EASTMAN: When we did the first Turtles book, we did a bunch of research at the local library to make sure we were as authentic as we could be.

AH:By now, there’ve been surely half a dozen derivatives of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles…

EASTMAN: I think there’s something like 20. The first one was kind of flattering. I’m thinking in the sense that imitation is the greatest form of flattery. I mean, we began with Miller and Kirby and used a lot of Miller parodies. We started with our book the way Sim started with Cerebus. He was drawing like Barry Smith and used a lot of Barry Smith parodies, and it attracted a lot of attention. We gave a sincere thanks to Miller and Kirby at the time, the two strongest influences. So, anyway, the first parody [Adolescent Radioactive Black-Belt Hamsters] was flattering. Then came another one, and another, and then it started to get old real quick. It was great to see all these people getting together forming companies, and putting out their own comics because they really wanted to. But I was kind of disappointed at the lack of originality. If they’re gonna get together to do their own comic and they’re really sincere about it, that’s great, but they should really look for something original. It started making us feel that people were putting this out because they just wanted to make a quick buck. On the other hand, there’s a book called Gnatrat, and it’s one of the best parodies I’ve seen, well-written, well-drawn.

LAIRD: This so-called black-and-white explosion is great because it allows a lot of other stuff, but through the open window comes stuff that’s embarrassing. I think the market can only take so may black-and-white books.

AH:What do you think is the future of independents?

LAIRD: I think it’s a great future as long as the comic stores hold up the direct sales market, and I can’t see that they won’t. Black-and-white comics from small companies are saleable; five years ago they were poison. Now distributors know that they can make money on them. The market will be there for some time if it can maintain this kind of frenetic expansion.

AH:What are some of your current favorite comics?

LAIRD: Personally, I really like Love & Rockets, Swamp Thing, Watchmen, and Cerebus.

EASTMAN:Dark Knight, Cerebus, Watchmen is out of sight, incredible stuff.

AH:Do you see your tastes changing as the variety of comics grows? Does being impressed with a Watchmen inspire you somehow?

EASTMAN: I think so.

LAIRD: Not that Kevin and I will ever be able to write like Alan Moore, but it’s very heartening to see the market’s potential. I can’t objectively judge the Turtles, Kevin and I are always trying to improve the writing and the drawing. Whether or not we are, I’ll leave up to the reader.

EASTMAN: The thing about the stuff that Alan Moore and others are doing is that it’s a big stretch from Turtles. Turtles are fun and exciting, we both have a bunch of stories to tell with the Turtles. But we have the desire to do something different, so we may alternate schedules on the book. One of the really great things about the market today as opposed to ten years ago or even five years ago is that there’s such a variety of stuff. There’s some very literate stuff, then there’s also things that have basic entertainment value. Nervous Rex would be a good example, basic fun stuff that’s there for entertainment, whereas before, you just had Marvel and DC, middle-of-the-road stuff. Now the market supports a whole variety of material. There’s something for every taste. You can’t really compare Love & Rockets and G.I. Joe [Laughter], but there’s obviously a market for each one. It’s an exciting time to be working.

AH:Looking at the new CBG Price Guide, I see that Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1 is going for $150 which is about what you made on the first issue. How do you feel about the speculation going on?

LAIRD: I have mixed feelings about the speculation as it exists now. When our book first came out, no one expected it to do anything. Most of the speculation on it is genuine; there were only 3000 printed and the readership is up to 125,000 now. It’s obviously a rare item. Now there’s actually some companies manufacturing scarce items. I think it’s real bogus and an insult to people’s intelligence to do a limited print run of a book specifically to make it “hot.”

EASTMAN: It really freaked us out that people were actually paying $25 or $30 for our book. We’ve been reprinting the books regularly. I think it’s great to attract an enormous amount of attention with speculation, but I want to know that people are reading Turtles and not just collecting it. The reason we keep reprinting them is for people who buy comics like I buy comics. You can see that some of my books are pretty beat up just because I’ve read them to death. We keep them at an affordable price, so that anyone can see them and read them.

LAIRD: We are not purposefully keeping our print runs down. That’s the furthest thing from our minds. There’s some really incredible bogus things going on in the industry; if you read the ads in the CBG, you can see. People are always speculating. It’s a fact of life that when you have something in limited supply, the demand will go up regardless of the intrinsic value. It’s a fact that there’s only 3000 copies [of #1]. That’s not a whole lot considering the buying power of the comics public. When the book was out, there were ads that went from $20 to $30 to $40 and the multiple copies price went up. I don’t think it was a result of the ads, but concurrent with them, the popularity was increasing. I don’t think it was artificial. What was the question? [Laughter]

AH:So is your uncle paid back, Kevin?

EASTMAN: And then some. He really made it possible.

LAIRD: We bought him a house in the Bahamas. [Laughter]

AH: Anything else you’d like to add? You’ve got a soapbox here.

LAIRD: I think Marvel should give Jack Kirby his artwork back immediately if not sooner, and Jim Shooter and Stan Lee should go on TV and publicly apologize.

EASTMAN: I agree with Peter. Not so harshly, but I see that it’s very wrong. Everyone in the industry knows it’s wrong and can plainly see that the artwork should be returned.

AH:Would either of you work for Marvel if Jim Shooter called you up tomorrow?

EASTMAN: To be perfectly honest, there are certain Marvel characters that I would like to work on. If he called tomorrow… I’m perfectly satisfied with the things we have going here.

LAIRD: The characters that I’d like to do just happen to be owned by DC, so I can say definitely no. Part of it is that I don’t have the time, but I’d also prefer an ethical revision of their policies before I do any work for them.

EASTMAN: Yeah, I can agree with that.

(See a reader’s response to this article here.)