By DANIEL PETERSEN

The robot knocked on every door but none opened. Rejected, he shuffled off to wait in a dark corner, vowing to return…

In the story of “Fugitoid,” set on a distant planet, a lightning-struck scientist awakes to discover his mind and soul trapped inside a robot’s chassis. The morally conscientious scientist spends most of his time on the run from people who want him to create a machine that can beam solid objects across space, which would certainly be put to destructive use.

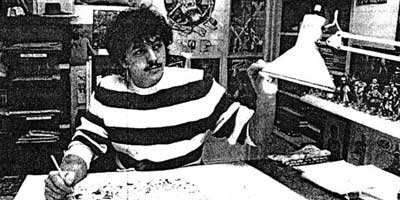

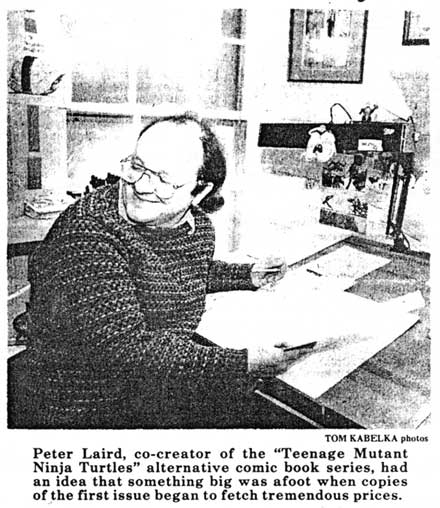

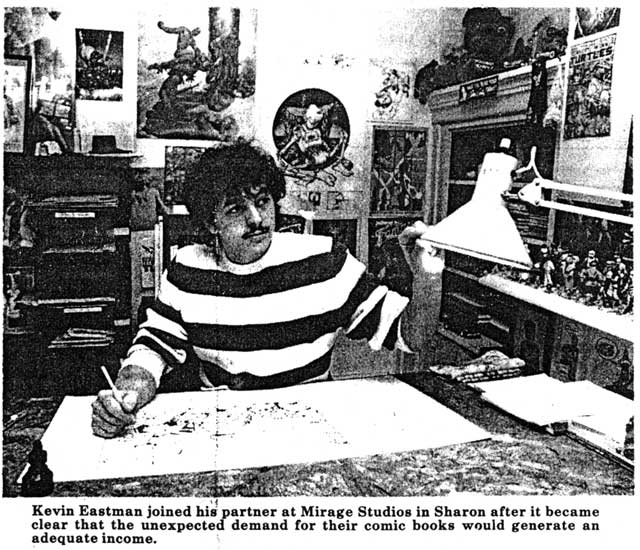

Conceived in September 1983, Fugitoid was the first comic book collaboration of Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird. Eastman and Laird are the founders of Mirage Studios, which opened in Dover, N.H., in December 1983 and moved to Sharon in 1984.

Hoping to find their personable metal man a home as a back-up feature in an established alternative comics publication, “we sent the first four chapters of Fugitoid around to all the major companies,” says Eastman, a 23-year-old native of Portland, Maine. None of the publishers bought the idea .

Not ready to pull the plug on the robot, Eastman and Laird focused their attention on another idea they had developed amidst the flurry of rejection slips: a story about four adventurous reptiles. “We thought it would be a better seller,” Laird says, so the pair established Mirage Studios and set out to produce their own publication. Satirically drawing on standard comic book conventions, the cartoonists published issue No. 1 of “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” in May 1984.

The first issue blended high adventure, science fiction, mysticism and just the right touch of camp. Laird says words alone cannot describe the turtles – named Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo and Donatello – or “the full magnitude of their gloriousness.” The 32-year-old native of North Adams., Mass., is jokingly boastful. He adds, somewhat more modestly, “So to speak.”

But as far as comic book collectors are concerned, the turtles are glorious – at least glorious enough to command more than $100 for a first-printing copy of issue No. 1 (there have been four printings so far). The March 28 edition of The Comic Buyer’s Guide sets the price of a mint-condition copy of the first printing at $125.

Eastman spent a year at the Portland School of Art and Laird holds a degree in printmaking from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, but each says his favorite school is between the covers of a comic book. After all, it was a comic book that brought them together in the first place.

“It was destiny,” Eastman recalls. One day in 1983, while he was riding a bus home from the Amherst supermarket where he worked, Eastman’s restless gaze fell upon a smudged copy of “Scat,” a tabloid comic magazine published not far away in Northampton, Mass. He was always “real interested in comics,” so he read it cover to cover.

“I went over to the address inside the cover with some of my own work. They said, ‘Hey, you draw just like this other guy’ and told me about Peter. I was impressed by his work. He was older and had 10 times more stuff.” ,

Eastman and Laird got together, and after striking out with the Fugitoid idea, they came up with the turtles. Laird describes their work as “more of a 50/50 collaboration.” Both artists participate in all aspects of production, from conception to rough sketching to dialogue to finished’ product. The books are printed in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

There were 3,000 copies in the first printing of issue No. 1. “They sold out right away,” Laird says. Encouraged by the demand for their turtles, the team published 6,000 copies in the second printing, and 35,000 and 60,000 copies in the third and fourth printings respectively. Issue No. 7 is scheduled to be released by March 30, and already, says Eastman. there are orders for 95,000 copies.

Fan-mail reveals a growing legion of devotees from as far afield as England and Malaysia.

The pair put the second issue together through the mail: Laird’s wife, Jeannine Atkins, had secured a job teaching English at Housatonic Valley Regional High School in Falls Village. In August 1984 she moved with her husband from Dover to Sharon, and Eastman went back to Portland.

Even though the team was separated, the future looked bright, Laird says. “It became obvious after the first printing of No. 2 that if we kept going at it, it would support us directly.” In February 1985 Eastman made the move to Sharon and full-swing production resumed. It’s been snowballing ever since. Even Fugitoid, who has appeared in the last two issues managed to get into the act.

Even though the team was separated, the future looked bright, Laird says. “It became obvious after the first printing of No. 2 that if we kept going at it, it would support us directly.” In February 1985 Eastman made the move to Sharon and full-swing production resumed. It’s been snowballing ever since. Even Fugitoid, who has appeared in the last two issues managed to get into the act.

And he’s not alone. Eastman and Laird are using their publication to “help out beginners” such as New Jersey cartoonist Michael Dooney, creator of “Gizmo,” and Tony Basilicato of New Haven, creator of “Prime Slime Tales.”

Laird’s happy to be part of the alternative comics renaissance. Unlike stores that sell Marvel, DC and other mainstream comic books, specialty shops (like My Mother Threw Mine Away in Torrington, F&S Comics and Fantasy Shop in New Milford, and Jim’s Comic Book Shop in Waterbury) don’t return what they don’t sell.

With mainstream comic books, Laird explains, newsstands can return unused books to the distributors. The distributors in turn send the books back to the publishers, which are equipped to “absorb the loss.” There’s no risk involved in ordering comic books from the giants of the industry. But buying quantities of comic books from smaller publishers who will not take returns could be risky.

In the specialty shops, or “the direct-sales market, dealers know what their customers will actually buy,” says Laird. ” If we had to take returns, we’d be in big trouble.” Laird hedges. “No – that’s not true. The turtles are a hot item. Our books always sell.”